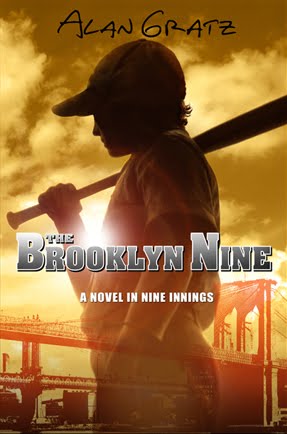

Read the First Chapter

Manhattan, New York, 1845

Nine months ago, Felix Schneider was the fastest boy in Bremen, Germany. Now he was the fastest boy in Manhattan, New York. He was so fast, in fact, the ship that had brought him to America arrived a day early.

Now he stood on first base, waiting to run.

“Put the poreen just about here, ya rawney Dutchman!” the Striker called. English was difficult enough for Felix to understand, and almost unintelligible when spoken by the Irish. But the “Dutchman” at Feeder-another German boy like Felix-didn’t need to understand Cormac’s words to know where he wanted him to throw the ball. He lobbed it toward the plate and the mick slapped the ball to the right side beyond first base.

Felix ran full out. His legs churned in the soft mud but his shoes gave him traction, propelling him toward second base. He was a race horse, a locomotive. The world was a blur when he ran, and he could feel his blood thumping through his veins like the steam pistons pounding out a rhythm on the fast ferry to Staten Island. Felix flew past the parcel that stood for second base and dug for third.

“Soak him!” one of the boys called. Felix glanced over his shoulder just in time to see an English boy hurl the baseball at him. He danced out of the way and the ball sailed past him, missing his vest by less than an inch. Felix laughed and charged on to third, turning on the cap there and heading for home.

“Soak the bloody devil!” one of the other micks cried. The ball came at Felix again, but this time the throw was well wide. He pounced on the rock at home plate with both feet and celebrated the point.

“Ace!” Felix cried. “Ace, ace, ace!”

“No it weren’t,” called one of the buckwheats, a boy just back from the Ohio territory. “You missed second base!”

Felix ran straight to second base to argue, and was met there by the boys on both teams.

“You’re out, ya plonker!” said one of the micks.

“The heck I was!” said Felix. He stepped forward to challenge the Irish boy, who stood a head taller. The Irish boy laughed.

“You sure you want to get them fancy ones and twos there muddy, Dutchman?”

The mick was on again about Felix’s shoes, which were better than everyone else’s. Felix’s father, a cobbler, had made them for him-sturdy brown leather lace-ups with good thick heels. They were the only thing he still had to remind him of his family back in Bremen.

The boys looked down at Felix’s shoes. That’s when they all saw Felix’s footprints in the wet earth. He’d missed second base by a foot.

“Three out, all out,” the buckwheat said.

Felix snatched the ball from the boy’s hand and plunked him hard in the shoulder with it.

“Run!” Felix cried.

The lot became a battlefield as both teams went back and forth, tagging each other and dashing for home to see who would earn the right to bat next. Felix had just ducked out of the way of a ball aimed for his head when someone grabbed him by the ear and stood him up.

“Felix Schneider!” his Uncle Albert yelled.

The game of tag ground to an abrupt halt and the boys shirked away as Felix’s uncle laid into him.

“I knew you would be here, you worthless boy! You should have been back an hour ago! Where is the parcel you were sent to deliver?”

Felix glanced meekly at second base.

“You’ve buried it in the mud!?” Felix’s uncle cuffed him. “If you’ve ruined those pieces, it’ll mean both our jobs! My family will be out on the streets, and you will never earn passage for yours. Is this why you stowed away aboard that ship? To come to America and play games?”

“N-no sir.”

Uncle Albert dragged Felix over to the parcel.

“Pick it up. Pick it up!”

“I didn’t step on it, see? I missed the bag-”

His uncle struck him again, and Felix said nothing more. With his speed he knew he still had plenty of time to deliver the fabric pieces, and time enough to go to the Neumans’, pick up their finished suits, and get them to Lord & Taylor by the close of business too. He also knew his uncle wouldn’t want to hear it.

“Now go. Go!” Uncle Albert told him. “If you were my son, I’d whip you!”

And if I were your son, thought Felix as he dashed off with the parcel, I’d run away to California.

Felix ran to where the Neumans lived on East 8th Street off Avenue B, in the heart of “Kleindeutschland,” Little Germany. Their tenement stood in the shadow of a fancier building facing the street on the same lot. The Neumans lived on the fourth floor, two brothers and their families squeezed into a one-family flat with three rooms and no windows. Felix hated visiting there. It made him think of those preachers who stood on street corners throughout Kleindeutschland yelling warnings of damnation and hell. As much as he disliked his uncle, Felix knew that but for Uncle Albert’s job as a cutter their own Kleindeutschland flat would look like this. Or worse.

One of the Neuman boys, not much older than Felix, met him at the door. Felix only knew him from deliveries and pick-ups-he’d never seen any of the Neuman boys playing on Little Germany’s streets or empty lots.

“Guten tag,” the boy said.

“Good morning,” said Felix. He held out the parcel. “I’ve got your new pieces.”

The boy let Felix into the room. It was hot and dark, and Neumans young and old sweated as they sewed cut pieces of cloth into suits around the dim light of four flickering candles. Herr Neuman, the family “foreman,” came forward to take the package from Felix.

“Danke schön,” Herr Neuman said.

“You’re welcome,” Felix said. “Bitte.”

Herr Neuman set the parcel on a table and opened it, counting out the pieces. He nodded to let Felix know everything was in order.

“Do you have anything for me to take back?” Felix asked. “Haben Sie noch etwas fertig?”

Herr Neuman held up a finger and went into another room. Felix waved to one or two of the women who looked up at him with weak smiles. Felix knew this wasn’t what they had expected when they’d come to America. It wasn’t what any of them had expected. Felix’s own father had talked of New York as a promised land, where everyone had good jobs and plenty to eat. “Manhattan is a city of three hundred thousand,” he’d said, “and half of those are men who will need a good pair of shoes.” Herr Neuman, a skilled tailor, had probably said the same thing to his family about the men in Manhattan needing suits.

What neither of them knew, of course, what none of the tailors and cobblers and haberdashers had known, was that those hundred and fifty-thousand men needed only five men to sell them suits and shoes: Mr. A.T. Stewart, Messrs. Lord and Taylor, and the brothers Brooks. They owned the three largest clothing stores in New York, massive, three and four story buildings Felix had gotten lost in more than once. Each had separate departments for men, women, and children, an army of clerks and fitters, and tables and tables of clothes, each outfit made not by a single tailor but by teams of men and women paid a fraction of what the suit cost. Felix, his Uncle Albert, the Neumans, they were all just cogs in the great department store machine. Uncle Albert did nothing now but cut cloth all day, but he was better off than the Neumans and hundreds of other families who sewed collars by candlelight sixteen hours a day, seven days a week. If they worked quickly, the Neumans might make twenty dollars a week sewing suits. Uncle Albert earned that by himself as a cutter.

Herr Neuman returned with a package of finished suits tied up with a string, and Felix left quickly under the pretense of hurrying them back to Lord & Taylor.

Felix ran past Tompkins Square Park to the Bowery, leaving Kleindeutschland and its crowded tenements and beer halls in his wake, but when he hit Broadway he slowed. This was Felix’s favorite part of the city. Here the pigs being driven to market strutted down the sidewalk alongside flashy American women wearing their big, brightly-colored dresses and ribbons. Gentlemen in serious gray suits hurried by with pocket watches in hand while ‘b’hoys’ with curled moustaches and red shirts and black silk ties mocked them from painters’ scaffolding and butcher shop doorways. Newsboys and street preachers shouted over each other on the corners. Buildings were torn down and rebuilt faster than Felix could keep up with them, and shootouts sometimes erupted in the streets. This wasn’t the New York of the Germans or the Irish or the English, it was the New York of Americans, and Felix tucked his package under his arm and fell into step with the bustle of the young city.

Uncle Albert had warned him not to dawdle on the way so he hurried along-fully intending to do his dawdling on the way back. At Lord & Taylor Felix delivered his package and picked up another, then made his way farther north on Broadway, adopting the American swagger of the lords, ladies, and swine. Felix found it easy to lose himself in Broadway’s foot traffic, to be swept up by the rush and hurry of Manhattan, to hear the clatter of iron horseshoes on cobblestones and the catcalls and insults of the city’s famously rude cabbies like a lullaby. On Broadway Felix was not a poor German Jew from Bremen walking the streets of a strange metropolis. Here, he was a New Yorker.

Felix made his way up Broadway to Madison Square, then down East 27th Street to the corner of Fourth Avenue where the New York Knickerbockers played baseball. He had found them by accident one day, following an oddly-dressed man wearing blue woolen pantaloons, a white flannel shirt, and a straw hat, and now he went by the lot every time he ventured this far north in case a game was underway.

Felix had been overjoyed to discover grown men playing at the same game he and his friends played-only it wasn’t exactly the same game. The Knickerbockers played three-out, all-out, but with more gentlemanly rules. For one thing, they didn’t chase each other in between innings to see which team would bat next. For another, they didn’t “soak” runners, trying to deliver the ball to the next base before the he could advance instead.

A game was underway when Felix arrived, and he joined three other spectators on a bank nearby, using the parcel with the cut cloth pieces as a seat cushion. The Striker at bat called for his pitch and smacked it to the outer field, where it was caught on the bounce.

“Hand out!” the Feeder cried, and the Striker tipped his cap and jogged merrily back to the sidelines.

Felix would have given all the sauerkraut in Kleindeutschland to be out there on the field with them. A new Striker took his place, and Felix imagined himself standing there in the blue and white uniform of the Knickerbockers, ready to deliver a base hit for his team.

The Striker bounced the first feed wide of first base, but strangely did not run.

“Foul ball,” the Feeder called, and the Striker returned home to bat again.

This is new, Felix thought, and he watched as the Feeder pitched again and again until the Striker was able to hit the ball in the field between first and third base. Letting “foul balls” go would certainly save a lot of chasing, Felix realized, and let the fielding team concentrate its defenders in front of the batter, instead of all around him. There was still a catcher, he noted, but mainly to receive the pitches the Striker chose not to hit.

This was less and less the three-out, all-out Felix knew, but he liked it.

The next Striker put a well-placed ball in between two of the outlying fielders and scampered toward second. The ball was thrown back in quickly, and appeared to reach second base at the same time as the runner. Neither team could tell whether the Striker was out or not, and the top-hatted judge at the table beyond third base admitted he hadn’t a clue. The judge came forward to examine the evidence, then threw his hands up in exasperation.

“Let us ask the young squire with the very nice shoes,” one of the Knickerbockers said. With a start, Felix realized the player was talking about him. The judge and three of the players came over to where he sat.

“I-I think the ball beat the Striker,” Felix told them.

“There we have it then,” said the Feeder.

“Agreed,” said the man in the top hat. “Umpire’s decision: hand out.”

“Three-out, all-out,” the Feeder said, smiling. The Striker tipped his cap and jogged out onto the field to take his position at a base, but the Feeder remained on the sidelines and extended his hand. Felix shook it.

“Alexander Cartwright,” the Feeder said. “And on behalf of the New York Knickerbocker Volunteer Fire Fighting Brigade, I’d like to thank you for your honest and impartial observation. I’ve seen you here before, haven’t I?”

Felix didn’t answer. He was transfixed by something over Cartwright’s shoulder, a towering plume of smoke billowing up from the rooftops of the city to the south of them.

Manhattan was on fire.